Finding Family History in Strange and Surprising Places

Biff Barnes

We moved to a new home recently. While placing a piece of furniture we’ve always referred to as my grandmother’s “secretary”, a piece whose top is a series of shelves enclosed in glass doors along with a flip down wooden door that offers a desk-like surface and the bottom is three drawers, I made a surprising discovery. As I changed the paper that lined one of the drawers a 2 ½ by 3 inch piece of cardstock popped out.

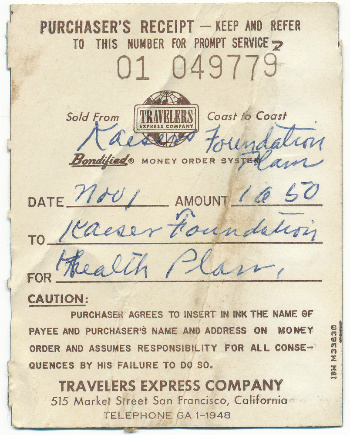

I grabbed it to toss it in the trash, but after I took a glance at the paper I stopped for a closer look. The card, with a piece of carbon paper attached to it, had probably laid in that drawer for almost 70 years. It was a receipt for a money order my grandmother had used to pay $10.50 for her November premium to the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan. The date said only November 1, but it was probably from sometime in the late 1940s.

I grabbed it to toss it in the trash, but after I took a glance at the paper I stopped for a closer look. The card, with a piece of carbon paper attached to it, had probably laid in that drawer for almost 70 years. It was a receipt for a money order my grandmother had used to pay $10.50 for her November premium to the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan. The date said only November 1, but it was probably from sometime in the late 1940s.

It was a piece of my grandmother’s history, but what did it tell me?

I began to think about that. $10.50 for health insurance? Wow! That seems pretty cheap, but what might it have seemed like to my grandmother? I arbitrarily decided to look at 1948 to try to decide. My grandmother was a widow in 1948. She was part of the 60% of Americans who described themselves as working class. Following her husband’s death in the twenties she had worked at the San Francisco department store, The Emporium, so her income was probably south of the U.S. median income of $3,120 per year. What did a $10.50 monthly bill mean to a person like grandmother? In 1948 a pound of hamburger cost 45 cents, a gallon of gas 16 cents, and a movie ticket 60 cents. I know my parents’ rent for a very nice two bedroom flat with living room, dining room and garage, in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood in the early 1950s (before it became famous) was $80 a month. So the Kaiser payment wasn’t insignificant to Grandma.

By the same token, my grandmother, like much of her generation, was emerging from hard times as the country put almost two decades of the Great Depression and World War II behind it. That a working class widow found room in her modest budget for health insurance indicated that better times were ahead. By 1955 the country’s median income had risen almost 54% to $4,800. People like Grandma realized that they could begin thinking beyond survival to modest levels of security provided by things like health insurance.

That was something new, as was the Kaiser Health Plan itself. The nation’s first large scale Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) (although nobody used that term until Paul Elwood, a government health care policy advisor, coined it in the early 1970s) had begun modestly enough in the 1930s. Dr. Paul Garfield set up a hospital near the Mojave Desert town of Desert Center, California, funded by payments from the employers of workers who were building the Colorado River Aqueduct. As that project wound down, industrialist Henry J. Kaiser, whose company was constructing the Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River in the state of Washington, partnered with Garfield to provide the same kind of prepaid care for his workers. When World War II began Kaiser brought thousands of workers to his Richmond, California shipyards and extended prepaid health coverage to them. As the war ended Kaiser and Garfield wanted the plan to continue so they made it available to the public in July, 1945. Grandma got in on the ground floor of the kind of health insurance coverage and services that the baby boomers came to take for granted.

My last thought as I looked at Grandma’s receipt was about the slower pace at which life moved in the late ‘40s. It was still largely a cash economy. My grandmother was using a money order from Traveler’s Express Company (today MoneyGram International) to pay a monthly bill. That meant going to the company’s office at 515 Market Street, not far from the Emporium where she worked, to buy the money order, then going to the post office to put it in the mail. Personal checking, credit cards and online banking were still somewhere in the future for most Americans.

As I reflected on the small piece of paper I thought of how many similar pieces of ephemera a family historian might have at hand which would offer insights into the lives of ancestors if only we take the time to think about them.

What might be lying in one of your drawers?