Does Creative Nonfiction Present a Danger to Writers?

Biff Barnes

Is there a danger for writers who employ the tools of creative nonfiction?

That’s a question worth some reflection. I have recommended that memoirists and family historians employ the techniques of creative non-fiction in telling their stories. The goal is to help them to bring documentary evidence and historical context to life by using literary tools like details of setting, scene and dialogue. So, should that advice come with a caveat?

I pose the question because two sources I read regularly, Richard Gilbert’s Blog, Narrative, and The Nation have both examined some potential pitfalls in creative nonfiction.

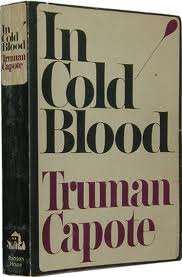

Gilbert in his post Janet Malcolm, Capote & Infamous examines Truman Capote and his prototype nonfiction novel In Cold Blood. Says Gilbert, “In Cold Blood opened the eyes of journalists to what immersion, scenes, dialogue, structure, plot, and characterization could do, and it impressed other novelists with what journalism could do. But one of the things that makes the book difficult to teach today, in journalism and creative nonfiction classes anyway, are Capote’s inventions. Apparently he created from whole cloth Smith’s apology on the gallows—others didn’t hear Smith say a thing. But Capote wanted others to see Smith sympathetically, hence, Smith’s rather well crafted contrition in In Cold Blood.”

In The Nation, Marian Markowitz Trials: On Janet Malcom. Markowitz calls Malcolm “…the most talented and incendiary woman journalist of her generation…” But she also examines Malcolm’s decade long legal battle with psychologist Jeffrey Masson who claimed that Malcolm had made up quotations in her book about him, In the Freud Archive. Courts eventually sided with Malcolm in the libel case in which she said the quotations were contained in a lost notebook, which she swore after the trial was found by a two year old granddaughter.

Both Gilbert and Markowitz explore the implications of another journalist who wound up in court, Joe McGinniss. Convicted murderer Jeffrey MacDonald, the subject of McGinniss’ book Fatal Vision, sued the writer for feigning friendship with him to gain his cooperation in writing the book. The suit was settled out of court after a mistrial.

What was responsible for the difficulties each writer faced? Markowitz’ conclusion of her piece about Malcolm offers a suggestion. She writes, “As Malcolm reminds us again and again, every narrator—whether he is a journalist, an attorney or merely a man sobbing his story to the bartender after a few too many—must attempt to shape a coherent story that reflects the reality he perceives but to which he can never be wholly faithful: ‘We go through life mishearing and mis-seeing and misunderstanding so that the stories we tell ourselves will add up.’”

How does a writer who seeks to employ scene and story in non-fiction avoid crossing a line into fiction?

For Lee Gutkind, who Vanity Fair called “the Godfather” of the creative nonfiction movement, it’s a simple matter. He says, “The word ‘creative’ refers simply to the use of literary craft in presenting nonfiction—that is, factually accurate prose about real people and events—in a compelling, vivid manner. To put it another way, creative nonfiction writers do not make things up; they make ideas and information that already exist more interesting and, often, more accessible.”