A False Memoir? Why Be Shocked?

Biff Barnes

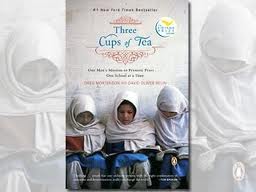

Last month CBS 60 Minutes ignited yet another controversy over a false memoir when Jon Krakauer, best-selling author and mountaineer, who wrote Into Thin Air and Into The Wild, speaking about Greg Mortenson’s book Three Cups of Tea, told 60 Minutes reporter Steve Croft, “It's a beautiful story, and it's a lie.”

The question of whether Mortenson’s book, which has produced speaking fees of $30,000 for the author and millions of dollars in donations for his Central Asia Institute, was part of an elaborate fraud is worth exploring.

But the hand ringing over Mortenson lying in his memoir is not.

False memoirs have emerged as a sub-genre of recent non-fiction. The Listverse website has even offered a list of the Top 10 Infamous Faked Memoirs. Ben Yagoda in his Memoir: A History demonstrated that the question of truth in memoir is not a new one. Jonathan Yardley captured Yagoda’s views in a Washington Post review: “Dating back to the 19th century, ‘the spate of unreliable memoirs [has] reflected an uncertainty and sometimes malleability about 'truth' that showed up in the wider culture as well. ‘On the one hand, we want "authenticity and credibility" in autobiographical writing; on the other, we want to be entertained, which can sometimes lead writers to exaggeration or invention.”

There’s an important distinction in the ways people write about their lives. Novelist Gore Vidal, in his own memoir Palimpsest, writes that “a memoir is how one remembers one’s own life, while an autobiography is history, requiring research, dates, facts double-checked.”

Some people writing their life stories have been quite forthright about showing themselves in a good light. The British statesman Winston Churchill said, “History will be kind to me for I intend to write it.” Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion said, “Anyone who believes you can’t change history has never tried to write his memoirs.” Almost any memoirist makes choices about how he will tell the story. That won’t always be the way someone else saw the same event.

Sam Tanehaus, the editor of the New York Times Book Review, in an NPR interview with Neal Conan on Talk of the Nation in the wake of the 60 Minutes expose, offered a more nuanced view on the problem of truth in memoirs. He said, “I think we need to be careful about calling it a lie. Or to put it another way, books are, of all descriptions, are filled with mistakes, errors and sometimes outright falsehoods. So I think some of it is just in the nature of memoir. You know, the word memoir derives from memory. And people's memories - my own foremost, I know, are, you know, unreliable.”

When a false memoir appears too many of us react like Major Renault in Casablanca who is “shocked” to find gambling going on at Rick’s even as he collects his winnings.

We’d be much better served if we could adopt Tanehaus’ perspective, “I think much of what's in most books is, to some extent, organized and orchestrated, if not invented, by the author. I don't read a book expecting to be given absolute fact. Maybe I should, but I don't.”