Stories To Tell Books BLOG

Filtering by Category: About Memoirs and Personal History Books

Memoir or Autobiography: Which One's for You?

Biff Barnes

What Makes a Good Memoir?

Biff Barnes

The Value of a Journal

Biff Barnes

Creating a Vivid Portrait of Distant Ancestors

Biff Barnes

How Family Historians Can Use Creative Nonfiction

Biff Barnes

Making Family History Books Interesting for Young Readers

Biff Barnes

In a recent post on the Grove Creek Family History Blog titled “What is Family History?” blogger Rayanne Melick posed a question most family historians face: How do we engage children and grandchildren in the family’s history? Melick explained that her son said to her, “Mom, whenever people ask you what you do for fun, you say family history. Do you ever notice that their eyes glaze over?”

Since the younger generations are the intended audience for most family historians, certainly most of the authors we work with, capturing children’s interest is essential.

So let’s look at what people who try to do this for a living – authors and editors of books for children – suggest.

“If you want to teach young readers about the Irish potato famine…tell them a story,” says Susan Brown Taylor author of several historical titles for children including Robert Brown Sails to Freedom.

Family history is, of course, rooted in fact, but as Reka Simonsen, Editor at Henry Holt and Company says, "Storytelling is storytelling. In nonfiction, the story happens to be true rather than invented, but the same rules apply: There should still he a strong story arc; there still has to be a problem that needs resolution; the characters have to be fully developed; there must be moments of dramatic tension and emotion of whatever kind appropriate to the events.”

Stories help kids learn to think by engaging their curiosity," says Shannon Barefield, Senior Editor at Lerner Publishing Group. "It makes readers ask, `Then what happened? Why?' and so on…storytelling techniques can bring to life a subject's significance in a way that just-the-facts writing can't always do. It's crucial for kids to learn the nuts-and-bolts facts of the Holocaust, for example, but to learn the human side of those events is critically important as well.”

Once engaged by family stories children may find themselves drawn into the pursuit of more knowledge about their ancestors. Judy O'Malley, former Editorial Director of Houghton Mifflin Books says, "I prefer to focus on the literature of fact books that tell the shaped story of what is known about lives and times, and that include the documentation of those facts that model for young readers how exciting authentic research can be. That leads them to read further and deeper, starting with the author's trail and following wherever their passion for the subject leads them.”

So as you plan and organize your family history book make sure it has plenty of family stories to appeal to the young audience for which it is intended.

Click here to read Rayanne Melick’s post, “What is Family History?”

Preserving Family Values With an Ethical Will

Biff Barnes

Family historians and memoirists seeking to pass on stories of their life experiences have rediscovered an old tool. The ethical will, is designed to provide a statement of the author’s accumulated values, beliefs and life lessons.

Originally described in the Talmud and the Bible, ethical wills have recently recommended by a diverse group of advocates. We agree with Scott Friedman and Alan Weinstein, writing for the American Bar Association who said, “A parent’s insight, knowledge and wisdom are the most important assets they can transfer to a child.”

Contemporary ethical wills differ in one important way from their traditional counterpart. The historical prototype was meant to be delivered to a person’s family after his death. But now ethical wills are written and presented to family members while the author is still alive.

Contemporary ethical wills, “...can be viewed as writing a love letter to your family,” said Barry Baines, the medical director of a Minneapolis hospice program and author of Ethical Wills: Putting Your Values on paper.

With extended families scattered across the country and even the globe, children don’t have the opportunity to hear the family stories that once were routinely repeated at grandma and grandpa’s dinner table. “Kids don’t grow up near their grandparents anymore,” said Karen Russell, founder of the non-profit National Grief Support Services. “Ethical wills are a way to have continuity when we don’t live with each other.”

There are no rules for writing an ethical will. “Just make sure it comes from the heart,” says Baines. Some of the things which are often part of an ethical will include:

- A statement of personal, religious or cultural values. This statement is often accompanied by examples of times when you did things to act on your values.

- Words of praise for those who deserve it

- An apology (if necessary)

- A request for forgiveness (if necessary)

- An offering of forgiveness (if necessary)

- An honest attempt to settle and resolve unresolved issues and disputes

- Words of wisdom. You might consider including things you have learned from both members of your family and from experience.

- Something(s) you are grateful for

- Your hopes for the future

Be careful to avoid lecturing people. “There’s a temptation to try to criticize, cause guilt, or tell people how to behave,” says Rabbi Jack Reimer co-author of So That Your Values Live On: Ethical Wills and How to Prepare Them.

Recently many people have expanded the idea of ethical wills to include family stories, history and formative or important personal experiences. The goal is to help future generations know the person who wrote the will and the world in which they lived. It is possible to make the elements of an ethical will a part of a Stories To Tell project.

Whatever form your ethical will might take, the financial advisors known as The Motley Fool captured its potential value when they said, “Photos can fade and inheritances are eventually spent. But an ethical will can provide inspiration to generations to come.”

Factual Family History - What Gets Lost?

Biff Barnes

Novelist Suzanne Berne’s new book Missing Lucile chronicles her search for meaning in her family’s history.

The experience is one that is not unfamiliar to genealogists and family historians. It might also be a cautionary tale they would be well to examine.

At the heart is her grandmother, Lucile, who died of cancer in her early forties. However, her father, a very young boy at the time, always believed that his mother had abandoned him. He said, “We were told she was gone. No one ever said where.”

Berne decides that her missing grandmother is "the Rosetta stone by which all subsequent family guilt and unhappiness could be decoded.” She sets out to unlock the family secrets by discovering what she can about Lucile’s story.

The result leads Julie Myerson, British novelist, columnist for the Financial Times and book reviewer for the BBC2’s Newsnight Review, to comment in her New York Times Book Review, “…this is my kind of book. Why, then, did I find it so arduous?”

The answer lies in Berne’s decision to tell the story not as a novelist but as a journalist or historian might do it. She commits herself to creating a factual account of the family’s history. She does imagine what might have happened or have been said, on occasions where all of the facts can’t be discovered. But each time, she stops the narrative to tell her reader what she’s doing.

The string of cautions and qualifiers leads Myerson to say, “I began to dread the sight of another lumpen passage dotted with Berne’s increasingly repetitive what-ifs and perhapses.”

That’s too bad. There is another way.

As Myerson commented, “Berne has said that she originally thought of writing her grandmother’s life as a novel, and you can see why. She’s a first-rate fiction writer, and the passages where she quits her detective-style ruminating and allows herself to bounce off on some imaginative tangent are by far the most vivid and successful in the book. Skies and flowers burst to life. History turns from black and white into Technicolor. You can smell the air, feel the breeze on your cheek. People have conversations that sound credible and alive. Who cares if they didn’t happen exactly as they’re written?”

This is a lesson for family historians. Family history is not academic history. The goal is to bring ancestors to life, and draw the reader into your book, by telling their stories. The factual record may not tell a person’s whole story. It’s incomplete, with gaps that can only be filled by using inference and imagination to round out the story. That process is the basis for a relatively new literary genre - creative non-fiction.

We can see the genre as it has been employed by masters in books like Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, Joyce Carol Oates’ On Boxing and George Plimpton’s Paper Lion.

Lee Gutkind, author and professor at Arizona State University, who Vanity Fair dubbed “the Godfather” of the creative non-fiction movement explains, “Although it sounds a bit affected and presumptuous, “creative nonfiction” precisely describes what the form is all about. The word ‘creative’ refers simply to the use of literary craft in presenting nonfiction—that is, factually accurate prose about real people and events—in a compelling, vivid manner. To put it another way, creative nonfiction writers do not make things up; they make ideas and information that already exist more interesting and, often, more accessible.”

When you write your own family history consider employing the techniques of creative non-fiction to tell your family’s stories. It will make the experience for your readers much more lively and interesting than relying only on what can be drawn from the facts. You can preserve the documentation by listing source material for the factual record in an appendix, for those who want to read it.

Click here to read Julie Myerson’s review of Missing Lucile.

Click here to read Lee Gutkind’s article What is Creative Non-Fiction?

Rock Memoirs - The Good and the Bad

Biff Barnes

I recently ran across a blog post on TheWrap which boasts it “Covers Hollywood” titled “Sex, Drugs & Publishing: Music Memoirs on a Rockin’ Roll.” Leading with the news that Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones has collected a $7.3 million advance for his just released memoir Life, the post notes that Rock memoirs have become a reliable cash cow for the publishers.

“They’re pretty easy to produce, and with an already built-in audience, fairly cost-effective,” a NYC-based publishing executive told TheWrap. “Pretty much all you have to do is interview the subject and just get a ghost(writer) to polish it into prose.”

Richards leads the Amazon preorder list.

That might lead to a bit of justified cynicism.

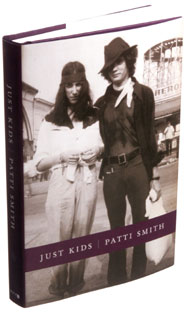

But on the same day I saw the post I heard Terri Gross on NPR interview singer Patti Smith, a punk icon, about her memoir Just Kids which has been nominated for a National Book Award in non-fiction. What a contrast.

Smith’s book recalls the late 60s and 70s in New York City and her relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe. Together they grow up in the avant-garde world of Andy Warhol and Allen Ginsburg.

Smith described their life together in this way, “We gathered our colored pencils and sheets of paper and drew like wild, feral children into the night, until, exhausted, we fell into bed.”

N.Y Times reviewer Tom Carson called Just Kids “…the most spellbinding and diverting portrait of funky-but-chic New York in the late ’60s and early ’70s that any alumnus has committed to print.”

The book deals with events before either Smith or Mapplethorpe had achieve the fame that would come later.

As Carson put it, “Just Kids captures a moment when Ms. Smith and Mapplethorpe were young, inseparable, perfectly bohemian and completely unknown, to the point in which a touristy couple in Washington Square Park spied them in the early autumn of 1967 and argued about whether they were worth a snapshot. The woman thought they looked like artists. The man disagreed, saying dismissively, “They’re just kids.”

It’s nice to see that the rock’n roll genre can produce art as well as schlock.

Click here to read the complete NY Times review of Just Kids

Click here to read TheWrap’s “Sex, Drugs & Publishing: Music Memoirs on a Rockin’ Roll”

Facts and Imagination in Memoir and Family History

Biff Barnes

In writing a memoir or family history is your goal a factual retelling of your memories of your life story or those of your ancestors? Or is it to imagine what it must have been like to be a particular person living at a particular time and place? Is your goal to write a personal history or a piece of creative non-fiction or to blend the two?

Richard Gilbert in his blog Narrative uses a recent interview in The Writer’s Chronicle to explore these questions. Faye Rapoport Des Pres conducted the interview with Michael Steinberg, author of Still Pitching, a memoir of growing up in New York in the 1950s.

At the core of a memoir [And I believe a family history as well.] are facts often based on extensive research. Says Steinberg, “Memoirs are set in real time and in real places, and they include real people and real events. Whatever else we think of the form, none of us would be inclined to trust a writer who fabricated those things. It goes without saying that a memoirist’s credibility, like the journalist’s, rests in part on those things that can be verified, even fact checked.”

But the memoirist or family historian must make an important decision about what to do with the facts. Are the facts a limit or a point of departure?

In Steinberg’s view a writer needs to add creative elements to the facts to get at the real story. He said, “…in my memoir Still Pitching I needed to re-imagine my childhood in order to better understand it. This was the only way I could express and articulate what it felt like to be that kid growing up in New York at that particular time in history (the ‘50s). In order to understand your past—in my case, childhood—you have to be able to imagine that past and the person you once were.

Choosing that course may depart from the strictly factual.

But by using the facts of the historical context in which the people about whom you write lived, you stand a much better chance of using you imagination to bring them to life for your reader.

Click here to read Richard Gilbert’s full post on Narrative.

Tweeting to Promote Holocaust Memoir

Biff Barnes

Ninety-one year old Willie Sterner is tweeting.

Sterner, a Holocaust survivor has written a memoir of his experiences, The Shadows Behind Me, which will be released today. As part of the book’s launch Sterner’s book will be tweeted in three daily updates each day for thirty days.

Sterner’s Twitter posts are part of a plan by Montreal’s Azrieli Foundation , which is publishing his book as a part of its Holocaust Survivors Memoir Program, to reach readers who would otherwise not be exposed to the stories of Holocaust survivors.

"Most Holocaust survivors can't find publishers for their memoirs," said Naomi Azrieli, chairperson and executive director of the foundation. "They write their memoirs because they don't want to lose their stories. We realized this is a great role for philanthropy, because there's no other way to get these stories out there."

Sterner’s memoir and others in the series will be sold in books stores and available for free download on the Azrieli Foundation website.

**********************************************************************************

The Azrieli Foundation’s effort to reach out to a new audience is one author’s seeking to promote their own books should consider. Social media can be a powerful in creating a buzz about a book. Plug Your Book! Online Marketing for Author’s by Steve Weber provides a comprehensive look at using other online tools to promote your book.

Click here to read the Montreal Gazette’s report on Sterner’s book launch.

Click here to visit the Azrieli Foundation website.

Good Advice on Book Marketing

Biff Barnes

If your goal is commercial publication, Kendra Bonnett’s List for Writers: 10 Tips for Marketing Your Book or eBook on her Women’s Memoirs Blog is well worth your time.

She provides a quick guide to some excellent resources for authors who want to promote books whether they have been published by traditional publishers or are self-published.

As I indicated in my comment on Women’s Memoirs, we’d also recommend a look at two books on marketing books: Aaron Shepard’s Aiming at Amazon and Steve Weber’s Plug Your Book: Online Book Marketing for Authors.

If your goal is to sell your book you need a marketing plan. If you don’t have one yet the resources above will help you create one. If you already have one, you might still want to take a look to see if there is something you might add to improve what you are already doing.

Click Here to read Kendra Bonnett’s List.

Interesting Examples of Topical Memoirs About Food

Biff Barnes

“I am a foodie; I always have been, and I’m not ashamed to admit it,” says Fliss on her blog All Lit Up as she opens a post titled Food For Thought: Three Food Memoirs. That was enough to get me – a fellow foodie - to read it. But the post contains some lessons for memoir and family history writers as well.

One of the most perplexing problems encountered by many people who want to write a memoir or family history is how to organize their books. The might do well to look at the three books Fliss reviews.

Cooking for Mr. Latte by Amanda Hesser

The book covers a period between when Hesser, a food writer, meets her future husband and their wedding day. The chapters were originally written as articles and each is followed by a series of recipes.

French Milk by Lucy Kinsley

This, says Fliss, is “a graphic novelesque travelogue of a monthlong vacation in Paris,” during which “Knisley is almost totally obsessed with food.”

Lunch in Paris by Elizabeth Bard

This memoir covers the first few years of Bard’s life after she moves to Paris. It is well-seasoned with recipes.

Each of the three books is an example of a writer successfully creating an interesting book by limiting the scope of their stories both chronologically and thematically. By organizing their books around a single topic the writers assured a unity of purpose and coherence.

These books are examples of an organizational technique that will work for both memoir and family history and for a multitude of topics.

Click here to read Fliss’ reviews.

Family Facts in Historical Context

Biff Barnes

People who want to create family history books often tell us that while the have done lots of factual research they have only a few family stories. What, they ask, can I do?

One of the ways to bring facts to life is to surround them with a historical context. If you don’t know many interesting details about your ancestor, try to find out what was going at the time and place where they lived.

You know that your family moved from Oklahoma to California in 1933, but the stories of their decision to leave Oklahoma and of their journey west have been lost. But there’s plenty of historical accounts of life in Dust Bowl Oklahoma and the migration of Okies to California. You could give your reader a sense of your ancestors experience by drawing upon stories told by people like them. You could make very effective use of literary passages like those in Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath.

You could use political events associated with a time and place in the same way to suggest what life for your ancestors was like. Nancy Hendrickson, a Contributing Editor of Family Tree Magazine provides an excellent example of how it’s done. You have only an isolated fact to work with. In Hendrickson’s example, “My family was included in the Putnam County, Missouri, 1860 federal census.” Here’s how she puts that single fact into a rich historical context:

In the fall of 1860, an Assistant U.S. Marshal traveled the rolling green hills of Putnam County, Missouri, questioning the people in every household. He asked their names and ages, occupation and birth place. As an agent of the Secretary of the Interior, he was charged with the responsibility of taking the Eighth U.S. Federal Census. He was called the enumerator. As he traveled the county, he probably got an earful of local politics—after all, the presidential election was only weeks away and with the South’s threat to leave the Union should Lincoln be elected, secession talk had to be in the wind. That, and the institution that James Russell Lowell called “the relic of a bygone world”—slavery. In this census year, a separate enumeration called a Slave Schedule, was also taken. This would be the last time in the country’s history that slaves would be counted.

The context makes the fact read like a story and helps us to understand the world in which the people listed in that census lived. It’s a way to help your reader share the experiences of the ancestors who people your book.

Whose Memoir is This Anyway?

Biff Barnes

So you’re concerned that your siblings have a different recollection of your family’s history than the one you want to put in your book. Your concern is not unique.

A melodrama of competing versions of a personal history is being played out today in the family of Ernest Hemmingway.

When Hemmingway committed suicide in 1961 his memoir, A Moveable Feast, was unfinished. Mary Hemmingway, his fourth wife reviewed the unfinished material with an editor from Scribner’s and assembled a book which was published in 1964.

Fast forward forty-five years. Hemmingway’s son, Patrick, succeeded Mary Hemmingway who had passed away as his father’s literary executor.

"I thought the original edition was just terrible about my mother," said Patrick. Mary Hemmingway had been the fourth Mrs. Hemmingway. Patrick’s mother was Pauline Pfeiffer, the second Mrs. Hemmingway. His concern was with the way the affair between Pauline and Hemmingway broke up his first marriage to Hadley Richardson.

So Patrick set out to create a revised edition. Patrick’s son, Sean, served as editor for the new version. Ernest Hemmingway had written several versions of his book and saved all the drafts. The new edition makes use of versions that Mary Hemmingway had ignored in the first edition.

In his notebooks Ernest Hemmingway had also said that the book was a work of fiction although conceding that fiction often contains true stories.

Robert Fulford summed the situation up in Canada’s National Post online. He wrote, “So Hemingway revised reality as he half-remembered it, and Mary selected from his versions the material she wanted, and Sean made some different decisions. The 2009 book turned out to be a revision of a revision of a revision.”

Your memoir or family history may never satisfy all of the members of your family. They may have their own memories of the events. If they want to share their version with others, they can write their own book. As for you, you might best be guided by novelist Gore Vidal’s comment on his own memoir, “a memoir is how one remembers one’s own life.”